Mirrors Edge: Still Alive

Spoiler warning: Minor scenario/level spoilers for Mirror’s Edge. Very little in the way of story spoilers, partially because there’s very little in the way of story.

Three days or two years: depending on how you look at it, that’s how long it took me to finish Mirror’s Edge. Though I’d managed to play up to Chapter 7 on the PS3, I didn’t really feel qualified to say whether the game had fulfilled its vision or not; some would argue that I’m still not qualified, given that I haven’t even tried any of the time trials yet. (I did manage to try a few out on the PS3 years back, though.)

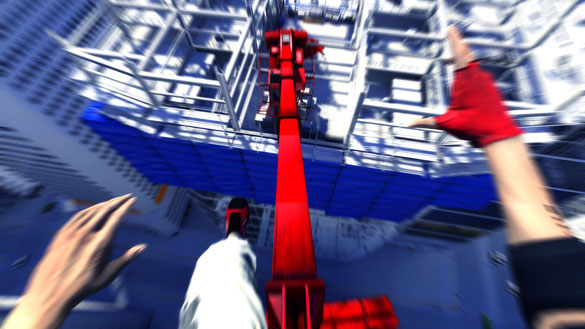

Having finished the game, did I ever feel the flow like the game clearly wants you to? At times, sure; chaining together a few smooth moves certainly did make me feel awesome. But like so many games, there’s a bit of a disconnect between what your character is supposed to be and what you, as a person sitting at a computer or on the couch, are capable of. I don’t have a good name for this phenomenon, but you’ve all encountered it at some point, or else you simply haven’t played enough games. It’s inherent to gaming itself, arguably, but it’s especially acute whenever you play a game with a strong protagonist—someone you’re supposed to identify with or become.

I’m talking, of course, about what happens when you fail. Miss a vital jump by inches, fail to grab a ledge at the right time, or stumble too far out on a ledge, and you die. Usually horribly, after tumbling from a great height into solid concrete. And then you start again from the last checkpoint. If only real life were so forgiving. But that’s the crux of the problem: real life isn’t forgiving at all. People were not meant to star in breathtaking war sequences where they shoot a ton of bad guys and walk away from explosions without looking at them; they’re meant to die from bullet wounds and shrapnel, or go home wondering if they can ever tell their families about what war is like, or maybe even live a perfectly well-adjusted life in the military, get their honorary discharge, and raise a family in peace. You’d believe a lot of outcomes for a solider in a war; none of them involve killing rooms full of insurgent soldiers with nothing but a bowie knife. And yet that’s what we do all the time in video games.

There’s nothing necessarily wrong with this sort of exaggeration. The Hurt Locker is a fine film to watch, but you probably don’t want to play the video game; too much introspection, not enough quick-time murder events, Activision or EA might say. You go to video games to escape the confines of real life, for the most part, so you want your player characters to be superhuman badasses. And that doesn’t just go for war games. Fallout: New Vegas turns you into either Jesus or Evil Jesus, able to dictate the future of the Mojave wasteland in ways no mere mortal ever could. Lots of RPGs are the same way: somehow you’re the guy or girl who can save the universe, and no one else. Whether it’s racing games, flight sims or adventure games, you’re often asked to perform impossible feats of daring that you would never in a million years try to do in real life because in a video game, you respawn, and in real life, some poor bastard gives the eulogy at your funeral.

We accept this bending of reality in video games for the most part, but people can only suspend their disbelief so far, and for some people that point comes a lot earlier than others. Meet one of those people: me. I’m not really a fan at all of trial and error gameplay; for whatever reason, I have trouble letting go of the expectation that any situation I’m faced with in a game should be solvable, or at least survivable, on the first try. Because if it’s not, then you’re basically asking the player to die at least once to figure out the solution to a problem, and in real life you don’t get second tries. You’ve created a situation no mortal human can hope to solve. Obviously, if you take a strict, hardline approach to this rule, you would probably never play a video game. A certain amount of failure is expected; otherwise games would cease to be challenging. But like I said, everyone draws the line somewhere. Mirror’s Edge often crosses it.

I think when detractors of the game talk about things like bad checkpoints (yes) or the frustrating combat system (yes) or the occasional failure to let you know where you should go (double yes), they’re not just talking about mechanical issues. People who disliked Mirror’s Edge seem to talk about the game sometimes as if it hated them. Or maybe that was just me. There was an inherent unfairness about how the game treated you sometimes; the fiftieth time you failed to get across a rooftop because a helicopter and six guards were all trying to kill you, you were probably thinking, “there’s no way Faith Connors could actually run through this hail of bullets to make the thirty-foot leap across this chasm and land precisely on this razor-thin ledge.” The bad combat (which turns out not to be so bad), the bad checkpoints (which turn out to be exactly that bad) and the bad waypointing (which turns out to be worse than you think) are actually just symptoms of bad scenario design. Too often, the game throws too much at you, expecting you to just figure out what to do at the right times without getting yourself shot in the head or thrown off the side of a building. For those able to face the challenge, it makes Mirror’s Edge a rewarding experience; for everyone else, it’s just a frustrating slideshow of horrific deaths, with very little in the way of valuable learning experiences that tell you what you could’ve done better.

The worst case of this comes after the part where I got stuck on the PS3, in the penultimate chapter: you have to find your way across several rooftops while being chased by several very aggressive runners. Mirror’s Edge contains several types of platforming scenarios: there’s the relaxed, freestyle sections where you’re left to your own devices to get from point A to B; there’s the puzzle sections, where you try to figure out how to get past a seemingly insurmountable obstacle in a secluded area without enemies; and then there’s the pursuit or combat sections, where you have to make it from point A to point B while several cops are shooting at you, chasing you, or both. The first two scenarios actually feel vaguely like what you imagine parkour would feel like: you size up your environment and try different options until you figure out something cool you can do to get somewhere you shouldn’t be. There’s a genuine sense of wonder when you figure out a solution to a puzzle scenario; you actually start thinking of buildings and pipes and scaffolding as handholds, launchpads and landing spots.

All that disappears in pursuit and combat scenarios. Combat is unsatisfying precisely because the unique proposition of the game doesn’t lie in the combat at all, but in playing with your environment. Under fire, you’re usually left to run frantically until you figure out the obvious solution. Either you find something highlighted in red and scramble for it; you stab at the hint key, get a vague idea of where you’re supposed to go, and run for it; or you die trying to make a jump that’s too far, or miss a crucial step in the jump-turn-jump sequence, or fail to hit a wall at the right angle, thus missing a wallrun trigger. And then you try again; but all you have is the knowledge of what not to do. Thanks to the incredible pressures of trying not to die, often you gain precious little information on what you’re supposed to do; the only recourse is to keep trying until you get it, slowly gathering information along the way until the puzzle unlocks.

Often, the puzzle relies on defeating well-armed enemies, which throws an extra dash of disbelief into the mix: yeah right, like anyone would try to jumpkick a cop in riot gear holding a light machine gun, let alone do it multiple times on an open rooftop. That’s just asking to be killed. But often there’s no other option, aside from grabbing a gun and shooting everyone—also somewhat unrealistic, given Faith’s background, but one you increasingly resort to as the easy way out. I pity the poor suckers who tried for the Test of Faith achievement, which requires that you not fire a single bullet at anyone for the entire game.

This piece might be a long way to go just to say the game was too hard, or had enough mechanical flaws to make it frustrating. But it’s not just that the game was frustrating in parts; it’s that it felt unfair in parts, and that’s a particular kind of difficulty you don’t see in other games. And the level to which Mirror’s Edge demands clairvoyance feels much higher than in other games, where the trial and error gameplay is usually because of some one-off contrivance like an ambush you couldn’t have seen coming. Mirror’s Edge repeatedly asks you to do the impossible; it’s no wonder it’s such a frustrating game.

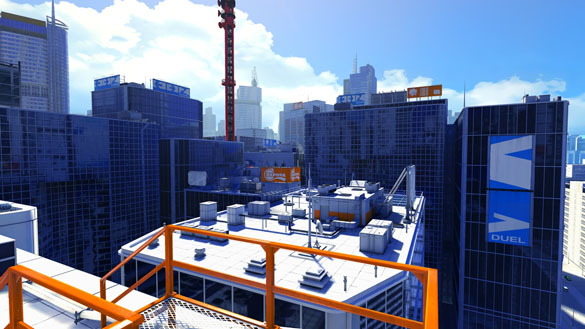

All that said, I still like the idea of Mirror’s Edge, and even the execution to a major extent. No other game does the crazy platforming stuff Mirror’s Edge does, let alone as well as DICE manages it, and very few games have the startlingly gorgeous art direction, either. When the sequel finally comes out—and EA says that it will, despite the game’s mixed critical and financial reception—I’ll be there, hoping for a game that focuses on all the amazing elements and less on the frustrating ones. But for the sake of my poor heart (and possibly my neighbours’ sanity), I’m putting the game down for now.

This originally appeared on Wesley’s Dear Game Diary tumblr.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Wesley Fok, rgbFilter. rgbFilter said: Mirrors Edge: Still Alive: Spoiler warning: Minor scenario/level spoilers for Mirror’s Edge. Very little in the … http://bit.ly/h6VEUW […]